BEGINNER’S GUIDE TO NUCLEAR WEAPONS

Start Here

Misconceptions and Myths

Path to a Nuclear Weapons-Free World

Numbers, Facts, and Figures

A Close Look at Nuclear War

Humanitarian Consequences and Social Justice

The Know Nukes Quiz

Glossary

Start Here

🕒 3 min read

Cloud from a nuclear test November 1, 1951 at The Nevada Test Site. National Archives photo no. 374-ANT-40-11-AQB-03-14.

The extraordinarily devastating force and deadly toxicity of nuclear weapons sets them apart from all other weapons. The detonation of a single nuclear bomb can kill hundreds of thousands and cause injury and illness for many more. A limited nuclear war can kill up to 2 billion through climatic effects that would cause global famine. A full scale nuclear war threatens humanity itself.

When the stakes are this high, it can be hard to wrap your head around what this means for you and how things could be different. That’s why Back from the Brink has created a Beginner’s Guide to Nuclear Weapons: a one-stop resource to help you get up to speed on the issue, so you can be informed and get engaged in meaningful ways.

What’s included in this guide

To prevent nuclear war, we must challenge the misconception that nuclear weapons make us safe. The doctrine of nuclear deterrence, which suggests adversaries will not risk attacking a nation that may retaliate with its nuclear weapons, is at its core a threat to commit mass murder. Deterrence also assumes that human beings and technology will never fail, and relies on rational state actors – leaders who are not prone to impulse and fully understand the devastating consequences of launching a nuclear attack. We’ve been lucky enough to have avoided accidental nuclear war so far, despite multiple close calls, but this is not guaranteed to last. Unpack this idea and find answers to your burning questions in the “Misconceptions and Myths” section.

The threat of nuclear war has loomed over the world for 80 years. Fortunately, history shows us that nations – even adversaries – have come together to address shared problems and that everyday people can play a part in changing things. Learn about these examples in “Path to a Nuclear Weapons-Free World,” which show us that it’s possible to reduce the number of nuclear weapons and even completely eliminate them.

This Ohio-class ballistic missile submarine can carry up to 20 submarine-launched ballistic missiles with multiple warheads. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Ashley Berumen. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Today, a new nuclear arms race is underway. The U.S. is pursuing plans to replace its entire arsenal of missiles, bombers, and submarines, even though nuclear weapons are ill equipped for the challenges of the 21st century like climate change, pandemics, and cyber threats. Our “Numbers, Facts, and Figures” section breaks down this excessive spending, as well as who has nuclear weapons and how many.

Many of our Cold War-era nuclear policies actually put us at heightened risk of nuclear war. Confronting this reality, and understanding what it really means to use a nuclear weapon, is crucial for building the will and support necessary to make the world safer. “A Close Look at Nuclear War” has details on today’s nuclear risk, how a nuclear war might start, and what happens when a bomb goes off.

A world free of nuclear weapons is not only safer, but also healthier and more just. Uranium mining on Navajo lands, testing on the Marshall Islands, and radioactive contamination around the Nevada Test Site are just a few examples of how building and testing nuclear weapons has harmed the environment and impacted the health of so many communities. Learn how nuclear weapons spread toxicity and disproportionately impact people of color, long before they explode in “Humanitarian Consequences and Social Justice.”

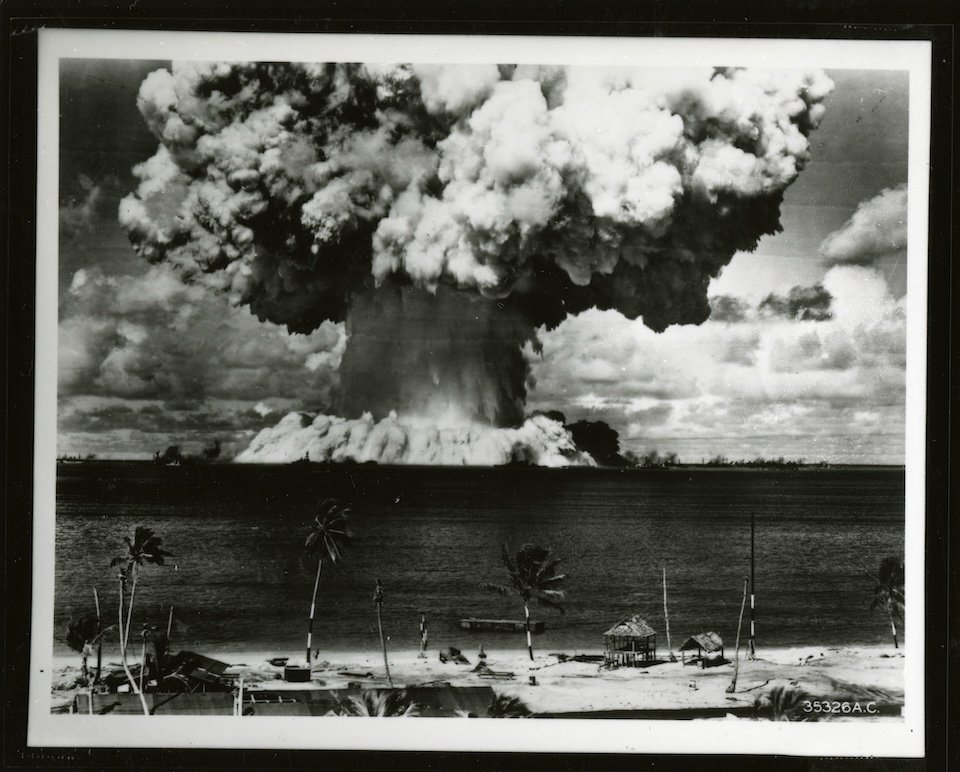

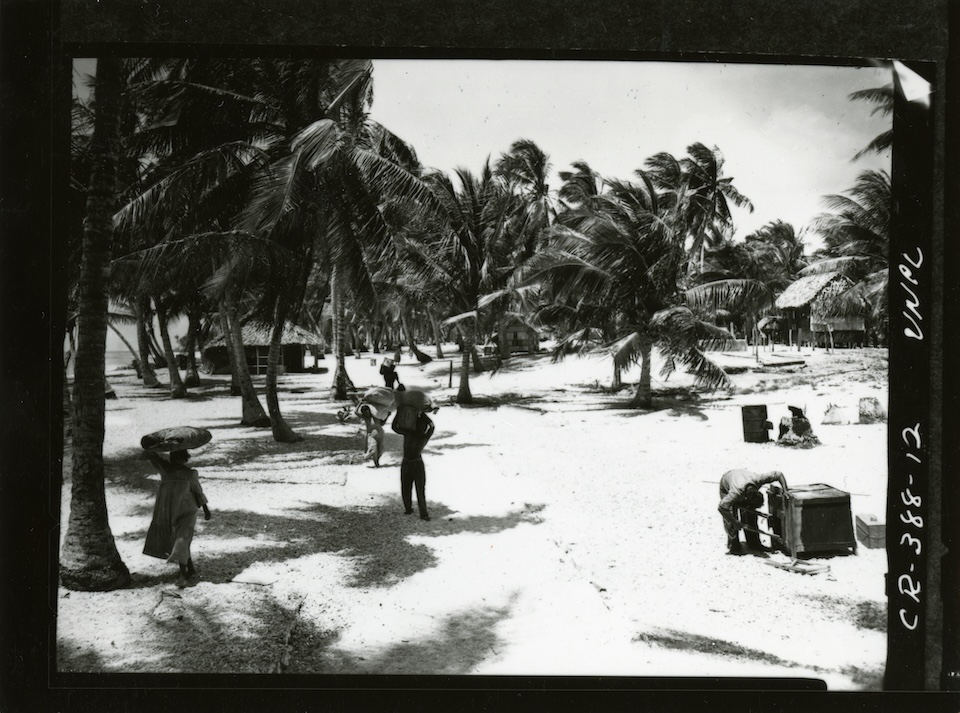

Even though residents of Bikini Island were forced to leave for nuclear tests, many still suffered health impacts from the radiation. National Archives photo no. 374-ANT-18-CR-109.

If you’re unsure what a specific word or phrase means, look it up in our glossary.

While world leaders gamble millions of lives on the hope that nuclear deterrence will hold, nobody is safe. But we can all play a role in changing things and building the world we deserve–one where we invest in human needs and a healthy planet over weapons of mass destruction.

This publication was made possible in part by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Misconceptions and Myths

🕒 6 min read

Medical experts practice providing medical care in a simulated chemical, biological, radioactive, nuclear, and explosive environment. U.S. Air Force photo by Joshua J. Garcia. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

You have questions, we have answers. The topics of nuclear war and weapons can quickly feel overwhelming and confusing, so here’s our take on some of the most common questions and concerns we hear.

In this section

1. Myth: Nuclear weapons make us safe. They deter other countries from attacking us.

2. Myth: The threat of nuclear war is a thing of the past.

3. Myth: We can stop a nuclear weapon attack.

4. Myth: We’re safe as long as we make sure nuclear weapons don’t fall into the wrong hands.

5. Myth: I don't need to worry about nuclear weapons right now.

Myth: Nuclear weapons make us safe. They deter other countries from attacking us.

Nuclear weapons are inherently destabilizing. By threatening massive harm to millions of people in a matter of minutes they introduce a high-stakes element to any conflict.

Claims that nuclear weapons make us safe are based on the theory of nuclear deterrence, which suggests that adversaries will not risk attacking a nation that may retaliate with nuclear weapons. But this is nothing more than a theory. Although nuclear weapons haven’t been used in war since the U.S. bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, it is impossible to prove that this is because of deterrence. More likely, it’s a fragile equilibrium sustained by luck and restraint—not a guarantee.

Meanwhile, we make the very dangerous gamble that deterrence is enough to keep countries from using their nuclear weapons. If the theory fails, it could very well mean the end of life on Earth as we know it.

But do nuclear weapons keep us safe from conventional attacks? We already know that the answer is no. The U.S., Britain, Israel, Pakistan, and India have all been attacked despite possessing nuclear weapons.

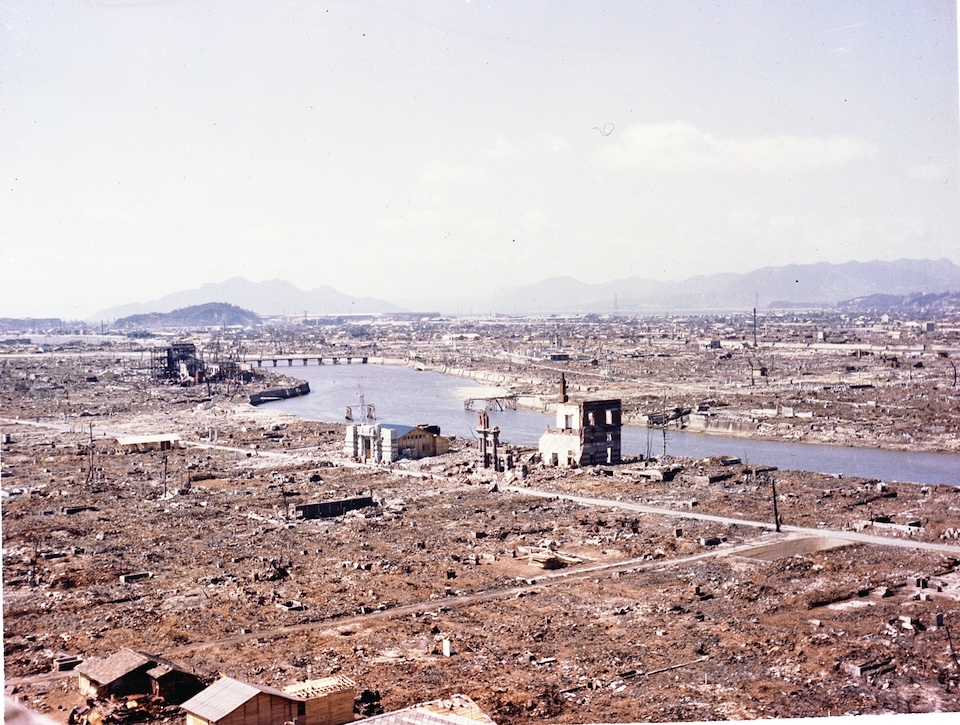

Hiroshima, Japan, after the U.S. bombed it in 1945. National Archives photo no. 342-C-K-6011.

Myth: The threat of nuclear war is a thing of the past.

After 80 years of nuclear weapons and no further nuclear use in war, it is tempting to think the risk has faded. But many experts say that, in reality, the world is closer to the nuclear brink than it ever has been.

Tensions are rising globally, due in part to climate change, and provocatory rhetoric is becoming commonplace. This, plus the fact that there are 9 nuclear powers that each bring their own interests to the table, makes the geopolitical landscape increasingly unstable. Leaders of countries possessing nuclear weapons have been threatening to use them in recent years.

An estimated 2,100 nuclear weapons around the world are kept ready to launch in an instant, building pressure for hasty or irrational decision-making. This means if there’s a misunderstanding or false alarm, it would be all too easy for a decision maker to order the launch of nuclear weapons without thinking it through. In fact, there have already been dozens of incidents–that are publicly known–where the United States has nearly triggered a nuclear disaster by mistake. While we are fortunate that each error was caught in time, the record shows that nuclear weapons systems – and the human beings that control them – can and do fail.

A ballistic missile submarine at Naval Base Guam in 2023. Navy Petty Officer 1st Class Joshua M. Tolbert.

Myth: We can stop a nuclear weapon attack.

It is highly unlikely that there will ever be a fully effective system to defend against a large scale nuclear missile attack. Intercontinental ballistic missiles are incredibly fast, giving defenders only minutes to calculate the missile’s trajectory and shoot it down. The warhead, the part of the missile with the nuclear weapon, is a small and difficult target to hit. Additionally, adversaries launching missiles have several tricks to evade interception, like launching decoy missiles or even deploying several warheads on the same missile.

Even though the U.S. has spent $400 billion in the last 70 years on ballistic missile defense projects, like former President Ronald Reagan’s “Star Wars” initiative, there is still no effective missile defense against a large scale missile attack. In 2025, the Trump administration proposed a massive increase in strategic missile defense funding known as the “Golden Dome,” intended to protect the United States by detecting and destroying threats like ballistic and cruise missiles. More effective than any missile defense system would be for countries that possess nuclear weapons to negotiate arsenal reductions and eventual elimination.

In the event of a large-scale missile attack, it is unlikely there could ever be an effective defense system that could stop such a barrage. But by pretending that effective defense systems exist, nuclear conflict might seem more manageable or winnable to decisionmakers and military planners. It also provides cover for world leaders to rattle their sabers in place of diplomacy, putting millions - if not billions - of lives in danger as they test the limits of nuclear deterrence theory.

A 2001 prototype of a ballistic missile interceptor. Courtesy Photo. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Myth: We’re safe as long as we make sure nuclear weapons don’t fall into the wrong hands.

No matter who has them, nuclear weapons pose a threat to humanity. There are no “good guys” with nuclear weapons or “bad guys” with nuclear weapons.The weapons themselves are the problem. They are unlike any other weapon–exponentially more lethal than conventional bombs, indiscriminate in who they kill, and destructive on a landscape-altering scale. Every time nuclear weapons factor into a conflict, tensions skyrocket. In such situations, nobody is guaranteed to think or act rationally. It’s all too likely that a miscalculation or misunderstanding could quickly escalate into a full-fledged nuclear war. In fact, the world has come alarmingly close to an accidental nuclear launch more than a few times. Each time, it was only through luck that the errors were discovered before someone launched a nuclear weapon that can’t be taken back.

Myth: I don't need to worry about nuclear weapons right now.

While funding for programs that provide basic human needs and security keep getting slashed, the United States spent $110.344 billion on nuclear weapons in 2024. Instead of investing in feeding people and keeping them safe, those tax dollars were spent on weapons we hope never to use. We already have enough nuclear weapons to destroy the world many times over.

Cloud from a nuclear test July 25, 1946 at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. National Archives photo no. 374-ANT-18-35326.

What if, instead of fueling a global nuclear arms race by spending hundreds of billions on a new generation of nuclear weapons, we freed up those resources to fund things like public infrastructure, housing, and healthcare?

Even if nuclear weapons are never again used in war, simply building and testing them has caused real harm to both people and the environment. Tests above ground produce dangerous nuclear fallout that cannot feasibly be contained, contaminating the environment and sickening living things as it scatters in the atmosphere. Underground tests, which became the norm after 1963, also pose risks through groundwater contamination and accidental venting. The spent nuclear fuel, which stays highly radioactive for tens of thousands of years, needs to be securely stored–a task much easier said than done.

People of color have long borne the brunt of these consequences. In the U.S., Navajo miners collecting uranium for the weapons, and those who live near the mines, have higher rates of illnesses like tuberculosis and lung cancer. Historically, nuclear tests have disproportionately affected Indigenous and Latinx communities, both in the U.S. and abroad. The radiation released during these tests has created generations of “downwinders” — people who became ill from living downwind of the sites.

Most countries ceased nuclear tests in the 1990s. North Korea is the sole exception, having carried out six tests between 2006 and 2017. Advisers to the Trump administration, however, have expressed interest in resuming nuclear tests, risking a new era of environmental harm and impacts to human health.

Path to a Nuclear Weapons-Free World

🕒 11 min read

The U.S. conducted around 1,000 nuclear tests between 1951 and 1992 at the Nevada Test Site. Photo by Ken Lund, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Since 1945, human beings have lived with the terrifying and unacceptable fact that nuclear weapons threaten humanity’s very existence, our future as a species. In the 80 years since the devastating U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, the world has been lucky enough to avoid another nuclear war. But countless individuals and communities have suffered and been harmed by nuclear weapons testing, manufacturing, production and the mining of uranium. It doesn’t have to be this way.

The complete elimination of all of the world’s existing nuclear weapons and a global prohibition of their possession, development, testing and use is both possible and realistic – technically and politically. Solving this existential problem is in humanity’s and the nations of the world’s collective self-interest.

In this section

1. Biological and chemical weapons are banned – nuclear weapons can be too

2. Political progress has already been made

3. Nations are already cooperating on shared problems

4. Technology and systems exist for verification and enforcement

5. It won’t happen unless the public understands the problem and demands change

6. Bending the arc – how the “impossible” became reality

Biological and chemical weapons are banned – nuclear weapons can be too

There are three types of weapons of mass destruction: biological, chemical, and nuclear. All of them cause widespread devastation, indiscriminate harm, and can spread uncontrollably. Of these, nuclear weapons are the only ones that haven't effectively been banned under international law, despite the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (learn more under "Political progress has already been made").

Airmen wearing chemical protective gear decontaminate weapons during an operational readiness inspection in 1985. National Archives photo no. 330-CFD-DF-ST-86-11754.

So, how did the world manage to ban entire categories of weapons? With legally binding treaties, known as the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), which has 187 parties, and the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which has 193 parties. The BWC and CWC ban the development, stockpiling, acquisition, retention, and production of biological and chemical weapons, respectively.

The BWC and the CWC encourage transparency; when parties join, they must declare the size of their stockpiles. Over time, they need to demonstrate what measures they’ve taken to dismantle the weapons, accounting for every devastating component. Both treaties allow members to submit compliance concerns, which get investigated, and the CWC has also written in a protocol for both routine and surprise inspections.

During World War I, people saw the horrific consequences of using chlorine gas, hydrogen cyanide, and anthrax on the battlefield. The Geneva Protocol made it a war crime to use biological and chemical weapons, and the BWC and CWC followed up by prohibiting their production, storage, and transfer as well. Both treaties have widespread support because the world understands that weapons of mass destruction are unacceptable.

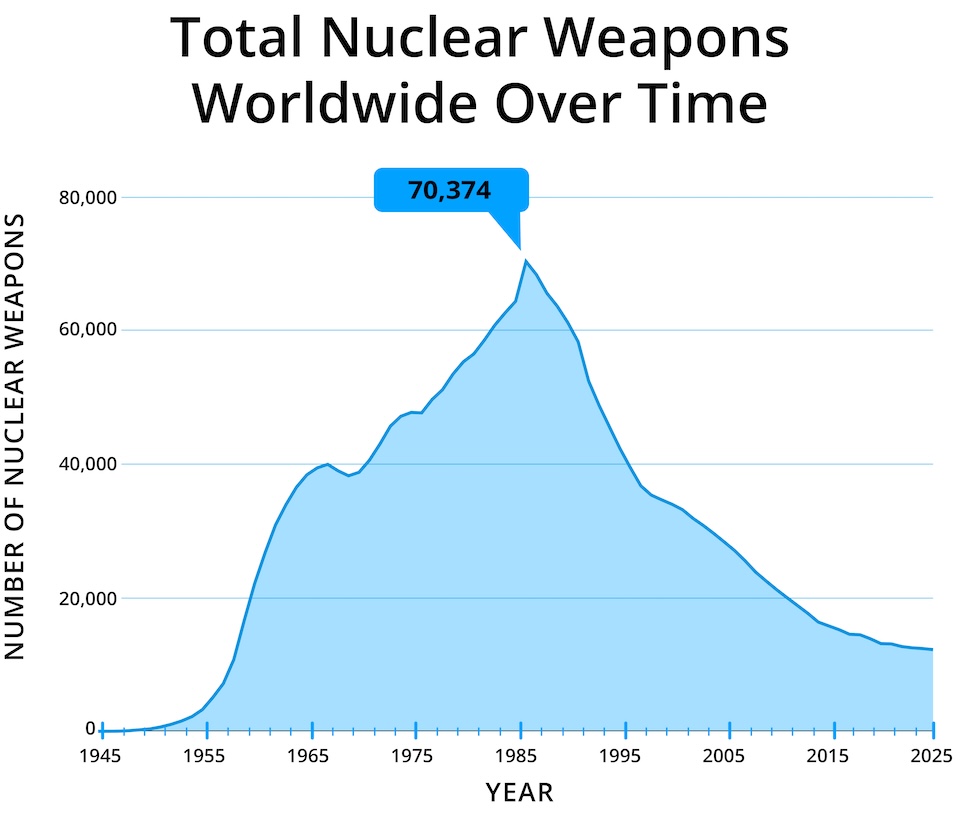

Political progress has already been made

The number of nuclear weapons worldwide has shrunk considerably from its peak of 70,374 in 1986 to today’s 12,241. Our rate of arms reductions is slowing down though, and the amount that remains could still end human civilization many times over. We need to continue reducing how many nuclear weapons there are in the world until that number is zero. Fortunately, the path forward has already been laid out for us–we just need to get back on it.

Numbers from the Federation of American Scientists. Graphic by Anthony Eyring.

Between 1960 and the early 1990s, several arms control and nuclear testing treaties contributed to our collective safety. Diplomatic agreements like the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT), Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), and New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) all helped by promoting peaceful cooperation over antagonization.

The LTBT, which has been in effect since 1963, bans nuclear tests in the atmosphere, outer space, and underwater. The CTBT goes a step further by banning nuclear explosions underground or for any purpose. It has been open for signatures since 1996, but hasn’t received enough ratifications to become binding. Despite this, there has been a voluntary moratorium on nuclear testing since the 1990s that all countries are abiding by except for North Korea, which has carried out six tests between 2006 and 2017.

The 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis forced many to confront the dangerous reality of nuclear war and provided momentum for the eventual negotiation of the NPT, which has been in effect since 1970. An international treaty with the goal of preventing the spread of nuclear weapons, the NPT requires countries without nuclear weapons to renounce ever developing or possessing nuclear weapons, a commitment that gets verified by an independent organization. In exchange, nuclear-armed nations share their peaceful nuclear technologies and vow to pursue nuclear disarmament in good faith.

There is, in fact, a global agreement to ban nuclear weapons. In 2017, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was negotiated and approved by 122 nations in a United Nations vote. It came into effect in 2021 after 50 countries ratified it. The TPNW prohibits nations from developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons, or allowing nuclear weapons to be stationed on their territory.

This historic agreement, representing an overwhelming majority of the world’s nations, came about as a result of years of persistent organizing and advocacy. Nuclear-armed nations are welcome and encouraged to join the TPNW; they would just need to agree to destroy their nuclear weapons according to a time-bound plan. Currently, none of its 94 signatories and 73 “states parties” – countries that have ratified the TPNW – are any of the world’s nine nuclear-armed nations.

A dismantled missile silo in Kazakhstan, photographed in 1995. National Archives photo no. 374-GTD-003-IMG0005.

Fortunately, history shows us it is possible for a country to give up nuclear weapons. South Africa produced its first nuclear weapon in 1982 and built 6 more before choosing to give them up and end its nuclear program in 1989.

Kazakhstan, used by the Soviet Union for nuclear testing from the 1940s to the 1990s, inherited more than a thousand nuclear weapons with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Harmed by decades of radiation from testing, the people of Kazakhstan protested against the tests and succeeded in closing a test site. Instead of choosing to keep their nuclear inheritance and becoming a nuclear power, the people of Kazakhstan decided they would be safer if they gave it up.

Much of the international community is already on board with a world free of nuclear weapons. There are five Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zones (NWFZs) covering much of the Southern Hemisphere, Central Asia, Mongolia, and Antarctica. Within these boundaries, nuclear weapons cannot be acquired, possessed, placed, or tested.

Then, there are the countries like Argentina, Brazil, South Korea, and others, that started developing nuclear weapons, but decided to stop. They reveal that not everyone will build up a nuclear arsenal simply because they can. In fact, the number of nations that have decided not to become a nuclear power outnumber how many have.

Nations are already cooperating on shared problems

The first assembly of the World Health Organization on 24 June, 1948, in Geneva. © World Health Organization/Archival.

Countries – even those that may otherwise be adversaries – already cooperate on myriad shared threats. There are international organizations coordinating activity on maritime rights, air travel, global health, and protecting the ozone layer.

These agreements allow the global community to work together for the sake of a healthier, more peaceful world. But they were not a given. Diplomats worked hard to align interests and incentives until they had a treaty that was in everybody’s best interest.

To achieve a world free of nuclear weapons, we must similarly be able to take everyone’s security and economic interests into account – even those that may be considered adversaries. Only this way will global security flashpoints be able to shift from confrontational to cooperative. Diplomatic agreements succeed when they serve the interests of every party involved. Nobody, not even authoritarian regimes, wants nuclear war.

Technology and systems exist for verification and enforcement

While it is not possible to un-invent nuclear weapons, we can effectively enforce a ban on their possession, development, deployment, and use. The United States, Russia, China and most developed nations have highly sophisticated intelligence gathering and monitoring capabilities, allowing them to effectively detect nuclear explosions from space and other covert bomb-making activities.

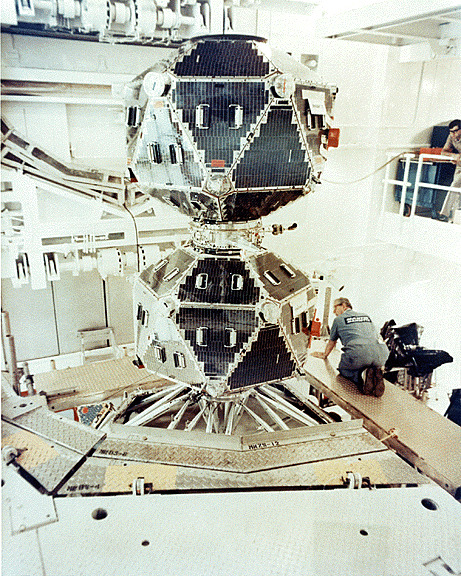

The Vela Satellites were developed in the 1960s to detect nuclear explosions from space. The pictured satellites, Vela 5A and 5B, were part of the program’s fifth launch in 1969. Photo courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory.

There are also organizations and systems in place to systematically verify treaty compliance. The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO) manages an international network of 321 monitoring stations and 16 laboratories hosted by 89 countries around the world. If a nation started conducting explosive tests – say, as part of a nuclear weapons development program – the CTBTO’s network would detect it.

Under Article 3 of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), each Non-Nuclear Weapon State is required to conclude a safeguards agreement with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Founded in 1957, The IAEA has proven highly capable at detecting the misuse of nuclear weapons material and technology. It runs regular inspections and thoroughly accounts for all nuclear material, and has successfully kept nuclear weapons out of the hands of most countries for more than 50 years.

One important, verifiable arms control treaty is set to expire in February 2026. The New START agreement, made between the United States and Russia in 2010, is a strong model for any global agreement to ban and prohibit nuclear weapons. It limits both sides to a maximum of 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear warheads and verifies compliance with data exchanges, required notifications, and on-site inspections.

Without New START, the U.S. would lose crucial access to information on Russia’s nuclear capabilities, and there would no longer be a limitation on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals. Extending this treaty would be an easy win for preventing an uncontrollable nuclear arms race.

It won’t happen unless the public understands the problem and demands change

Today’s movement to abolish nuclear weapons, photographed at the Third Meeting of States Parties of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2025. ICAN Photo by Darren Ortiz.

In the early 1980s, the general public’s growing concern about the possibility of nuclear war gave birth to the Nuclear Freeze movement in the U.S. Everyday people signed petitions, met with their neighbors, and took to the streets, calling for an agreement between the U.S. and Soviet Union to stop testing, producing, and deploying nuclear weapons.

The Nuclear Freeze movement started with town meetings but quickly gained momentum across the nation. By June of 1982, an estimated one million people gathered in New York City for an anti-nuclear arms demonstration–the largest peace rally in U.S. history. In the fall of that year, Freeze referendums appeared on the ballot in 10 states and 37 cities and counties; they passed in 8 states and 34 municipalities. In May, 1983, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a Nuclear Freeze resolution. Over time, the movement gathered endorsements from all major religious bodies in the U.S., hundreds of organizations, and 25 labor unions – much like Back from the Brink is doing today.

Across the pond, the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament had been organizing to abolish nuclear weapons since the late 1950s. Their first march took place in 1958, in London, with thousands in attendance. This activism gave rise in the 1980s to the Europe-wide European Nuclear Disarmament movement. In October 1983, 3 million people across western Europe gathered to protest the placement of nuclear missiles in Europe and call for an end to the arms race.

The widespread outcry pressured leaders to adopt the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which required the U.S. and Soviet Union to get rid of missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers. This agreement effectively removed many nuclear-armed missiles being stationed in Western Europe.

Today, Back from the Brink (BftB) and scores of other nuclear disarmament campaigners and civil society organizations around the world are shaping a new movement that is giving voice and agency to people. Our campaign provides a platform, resources, and sense of community allowing any individual, organization, or elected official to get engaged and make a real difference in their communities. Because nuclear weapons are a local issue affecting all of us, all of us should have a voice and say. And we say it’s time to get rid of them.

Bending the arc – how the “impossible” became reality

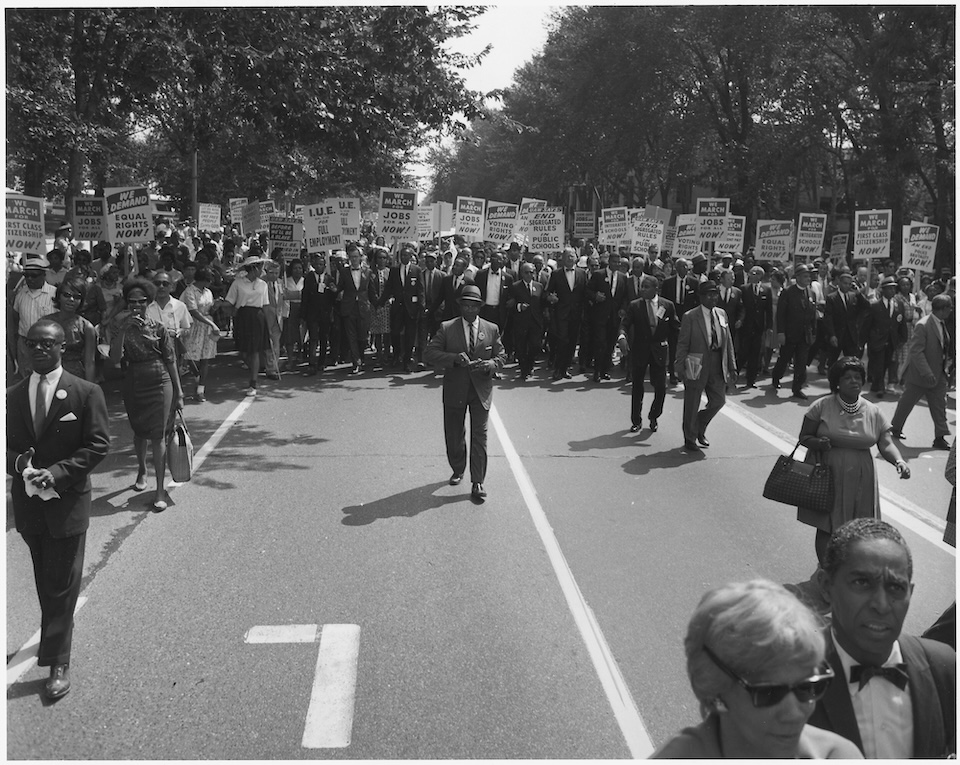

Leaders of the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. National Archives photo no. 306-SSM-4C-35-4.

After living in a world with nuclear weapons for more than 80 years, it can be hard to believe they could ever go away. But throughout history, people have succeeded in making social and political changes that were once thought to be impossible.

Looking back today, it may feel like the accomplishments of the civil rights movement were inevitable, when in fact it faced serious doubt at the time. When Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington, a Gallup poll found 60% of white people believed it would not accomplish anything and only cause violence.

This skepticism actually grew a year later, with 74% of Americans saying that mass demonstrations hurt the cause for racial equality. But only two months after that second poll, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed. Five years later, another Gallup poll found 63% of Americans believed nonviolent demonstrations could help black Americans win civil rights.

Protesting and activism have succeeded time and again in swaying public opinion and building political will for change. These methods have made a difference in so many issues: the abolition of slavery, marriage equality, and women’s right to vote. Plenty of people once thought these could never happen, until – through persistence and organizing – it did.

Numbers, Facts, and Figures

🕒 6 min read

An unarmed Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic Missile launches during a test in 2021. Air Force Staff Sgt. Brittany E. N. Murphy.

Numbers current as of July 2025.

Which countries have nuclear weapons? How many nuclear weapons are there in the world?

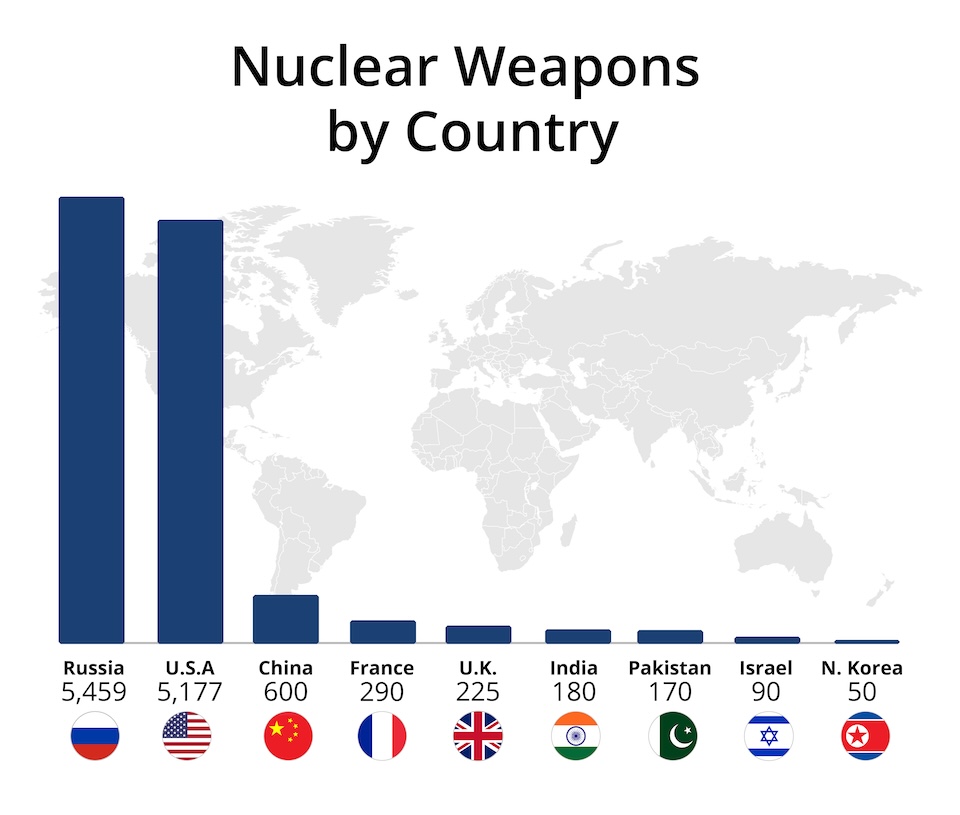

Although the global nuclear stockpile is smaller now than it was during the Cold War, when it peaked at 70,300, there are still 12,241 nuclear weapons in the world. Of these, around 9,700 are in active military service (either deployed or in the military stockpile, where they could easily become deployed). The rest are slated to be dismantled.

The nine countries with nuclear weapons are: the United States, Russia, China, France, the United Kingdom, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea.

Numbers from the Federation of American Scientists. Graphic by Anthony Eyring.

How much does the U.S. spend on nuclear weapons?

In 2024, the United States spent $110.3 billion dollars on nuclear weapons. This spending covered not only on warhead maintenance, but also related costs like environmental cleanup and missile defense. Here’s how that money was divided up.

| Source | Purpose | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| U.S. Department of Defense | Modernizing and maintaining nuclear weapons | $49.2 billion |

| U.S. Department of Defense | Missile Defeat and Defense | $28.4 billion |

| U.S. Department of Energy and National Nuclear Security Administration | Environmental cleanup from nuclear weapons activities | $32.7 billion |

Swipe left on the table above to see the column with dollar amounts.

In 2025, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office estimated that U.S. spending on nuclear weapons over the next decade will total $946 billion. This is a $190 billion increase from its previous prediction for spending from 2022 to 2032.

Numbers from the 2025 Nuclear Weapons Programs Tax Calculator and Congressional Budget Office.

How many nuclear weapons does the U.S. have?

In 1967, the U.S. nuclear stockpile peaked at 31,255. As of January, 2025, the United States has roughly 5,177 nuclear warheads. Of these,1,770 are deployed and another 1,930 could be deployed out of the military stockpile on short notice. Finally, 1,477 are retired and waiting to be dismantled.

Most of the nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal are strategic nuclear weapons, which are designed to swiftly decimate an opponent by destroying military bases, key infrastructure, entire cities, and many millions of people. Around 200 are considered “tactical” nuclear weapons, which are seen as more usable, as they have less range and produce a less powerful explosion than strategic nuclear weapons. Some tactical nuclear weapons, however, are more powerful than the bomb used in Hiroshima.

An unarmed trident missile launches from a submarine in 2020. Navy Petty Officer 2nd Class Thomas Gooley.

The U.S. nuclear arsenal includes three methods of delivery via the land, sea, and air. The weapons can be launched from intercontinental ballistic missiles housed in underground silos, from the sea by submarines, and from the air by bomber planes. Analysis from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists estimates that the U.S. stores its nuclear weapons across 11 U.S. states and five European countries.

An arms control treaty between the U.S. and Russia, known as The New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), has limited how many long-range nuclear weapons either country can deploy. It is set to expire February 5, 2026.

See the table below to learn more about the United States’ nuclear arsenal.

| Status | Number |

|---|---|

| Nuclear warheads on intercontinental ballistic missiles, which launch from underground silos. In position for military action (deployed). | 400 |

| Nuclear warheads on submarine-based ballistic missiles, which launch from underwater. In position for military action (deployed). | 970 |

| Nuclear warheads at air force bomber bases to be dropped by military aircraft. In position for military action (deployed). | 300 |

| Tactical nuclear weapons at aircraft bases in Europe. In position for military action (deployed). | 100 |

| Nuclear warheads held in reserve–they are not yet in position for military action, but could be loaded onto missiles and aircraft. | 1,930 |

How would the U.S. launch a nuclear weapon?

In the United States, the President is the only person who has the authority to order the launch of nuclear weapons. The President may confer with advisors or military staff including the Secretary of Defense and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff regarding such a decision. But the President is not required to consult anyone–and once the President has ordered a launch, no one has the authority to cancel it. This is known as sole authority.

The Sea Based X-Band Radar, photographed in 2006, detects ballistic missiles. Courtesy Photo. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

If the U.S. detects an incoming missile, the country’s “launch-on-warning” posture enables a retaliatory nuclear strike while the adversary’s missiles are still in the air. To achieve this, the U.S. keeps nearly one thousand nuclear weapons on nuclear submarines and in land-based silos on hair-trigger alert–they are staffed around the clock and ready to launch just minutes after receiving the order.

Once the U.S. nuclear command and control system detects an incoming nuclear attack, the President in most cases may only have a matter of minutes to decide whether to launch a nuclear counter-attack. This leaves little time for the President to even verify whether a warning is accurate before making a decision that could change -- and destroy much of -- the world. Since the atomic age began in 1945, there have been numerous nuclear close calls when humans or computer systems mistakenly believed that the United States was facing imminent nuclear attack.

After the president decides, they must give orders for how many nuclear weapons will be launched, and where they will go. A set of documents called the Black Book gives the President a menu of nuclear strike options to choose from. This list, along with secure communication equipment to reach the National Military Command Center, are kept inside a briefcase known as the nuclear football. The football also has a laminated card called “the biscuit,” with unique alphanumeric codes used to authenticate the President’s identity, and is carried by a military aide who stays close to the president wherever they go.

U.S. nuclear policy also leaves the possibility of first use on the table. In this scenario, the President could order a pre-emptive nuclear strike. Once again, nobody but the president can order a nuclear attack, and nobody can rescind a launch if the president has ordered it. Although only Congress has the authority to officially declare war, the President can still unilaterally decide to launch a nuclear weapon–effectively a declaration of war.

🔎 Additional resource

To learn about the process, read “How to Launch a Nuclear Weapon” from the Outrider Foundation.

A Close Look at Nuclear War

🕒 5 min read

This mock airplane was used in a weapons of mass destruction exercise in 2003. Photo by Sgt. 1st Class Doug Sample. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Nuclear war can feel both impossible and too terrifying to imagine. But the truth is, we know quite a lot about how it is likely to start and what it would look like. When many more people understand these harsh and terrifying realities, we will be able to make true change – by building the will and support needed to change dangerous policies and eventually achieve a world free of nuclear weapons.

In this section

1. Can nuclear war really happen?

2. Have we come close to nuclear war before?

3. What happens if a country uses just one “small” nuclear weapon?

4. Would the U.S. be able to stop an incoming missile?

5. What would happen if a country launched a nuclear bomb against a major city?

6. Can you survive a nuclear explosion?

7. What happened after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

8. What happens after a nuclear war?

Can nuclear war really happen?

Yes. Rising tensions around the world and a growing tendency towards provocatory rhetoric contribute to unrest. When you add in outdated nuclear policies, fallible human beings, and technology that allow for false alarms and prioritize hasty decisions, it greatly increases the risk that a conflict could become nuclear. The following fact sheet from Back from the Brink dives into the factors that make nuclear war an unnerving possibility.

🔎 Additional resource

Read "Can Nuclear War Really Happen?” from Back from the Brink.

Have we come close to nuclear war before?

Yes. False alarms with nuclear weapons have been disturbingly common, and it is largely luck that averted catastrophe. Below, a fact sheet from the Union of Concerned Scientists details these past incidents and explores their causes, from technical malfunctions to human error.

🔎 Additional resource

Read “Close Calls with Nuclear Weapons” from the Union of Concerned Scientists.

What happens if a country uses just one “small” nuclear weapon?

This F15-E fighter plane is carrying a tactical nuclear weapon as part of a test in 2021. Photo by 1st Lt. Jonathan Carkhuff. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

The United States and Russia both have tactical nuclear weapons, which produce smaller explosions compared to other nuclear weapons. But tactical nuclear weapons are still far deadlier than any conventional weapon and can even be several times more powerful than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Despite this, military strategists often consider tactical nuclear weapons to be more “usable,” wagering that their smaller explosions are less likely to provoke nuclear retaliation. Unfortunately, researchers have found this assumption to be dubious. A simulation from Princeton University, based on current nuclear weapons policy, shows what happens after a country launches one tactical nuclear weapon.

🔎 Additional resource

Check out the "Plan A" simulation from Princeton University.

Would the U.S. be able to stop an incoming missile?

Not necessarily. Although missile defense systems, developed by the U.S. and Israel, can successfully stop some missiles, they are not guaranteed to succeed or stop a large-scale attack. Adversaries launching missiles can deploy a number of tactics that can trick and evade attempts at interception. In the event of a large-scale missile attack, there is no existing defense system that can effectively stop the barrage. The following article from the New York Times explains how missile defense systems work, and why they often fail.

🔎 Additional resource

Read “How Missile Defense Works (and Why It Fails)” from the New York Times.

What would happen if a country launched a nuclear bomb against a major city?

A nuclear weapon can quickly destroy an entire city and kill millions of people. Almost instantaneously, the explosion would create a fireball vaporizing everything in the few square miles around the blast, depending on the size of the bomb. A few more miles out, winds blowing up to 600 miles an hour and heat up to 800 degrees Fahrenheit would destroy buildings, melt cars, and ignite everything flammable. The firestorm would not only cause serious burns, but also suffocation, by consuming all the oxygen. Over the following months, radiation sickness and radioactive contamination would continue to claim victims.

🔎 Additional resource

Watch “What would happen if a country launched a nuclear bomb against a major city?” from Back from the Brink.

Read what would happen if thousands of nuclear bombs were exchanged in "Would Nuclear War Between the U.S. and Russia End Human Civilization?" from Back from the Brink.

Can you survive a nuclear explosion?

If anyone was still alive after a nuclear bomb was used on their city, they would probably be very seriously injured and burned. But it would be nearly impossible to receive help, since any health, transportation, communication, and firefighting infrastructure in the blast zone would have been destroyed. In the event that there are first responders still alive, they would not only be overwhelmed by the number of casualties, but also be risking their own lives by exposing themselves to high levels of radiation.

🔎 Additional resource

Read “No adequate response capacity” from the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

What happened after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

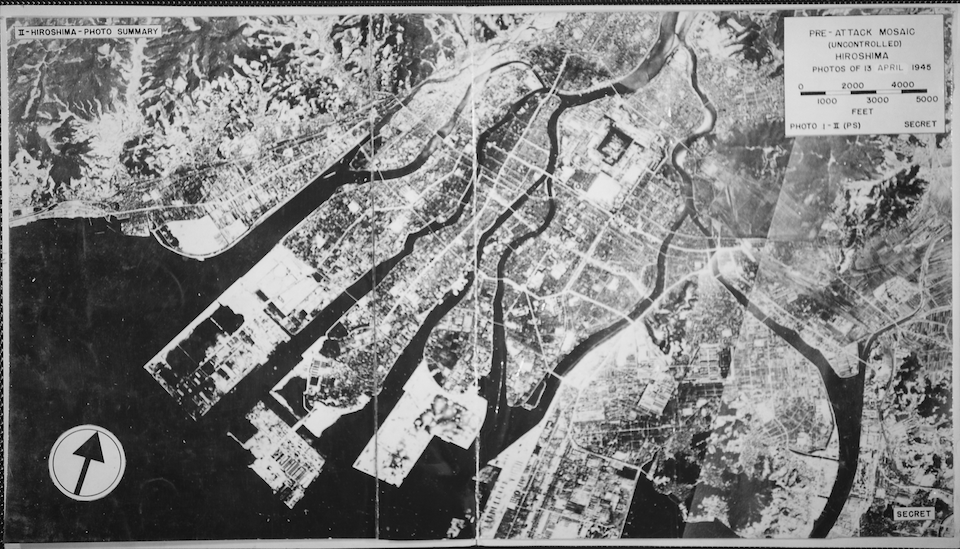

Use the slider above to compare photos of Hiroshima before and after the U.S. bombing in 1945.

Mosaic photos of Hiroshima before and after the U.S. bombing in 1945. National Archives photos no. 243-HP-1(3) and 243-HP-1(4).

The story of Hiroshima and Nagasaki continues long after their bombings at the end of World War II. While the casualties in the immediate aftermath are horrific on their own, an article published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists shows how initial estimates fail to capture the full scale of devastation.

🔎 Additional resources

Read “Counting the dead at Hiroshima and Nagasaki” by Alex Wellerstein.

What happens after a nuclear war?

Climatic effects from nuclear weapons explosions can cause mass starvation, ecological collapse, and threaten the future of humanity itself. A chilling video from Kurzgesagt describes what this posited future, known as nuclear winter, may look like.

🔎 Additional resources

Watch “What Happens AFTER Nuclear War?” by Kurzgesagt.

For a detailed dive into how nuclear war would play out, read “Nuclear War: A Scenario” by Annie Jacobsen.

Humanitarian Consequences and Social Justice

🕒 8 min read

In the 1954 “Castle Bravo” test, the U.S. detonated a thermonuclear weapon 1,000 times more powerful than the one they had used on Hiroshima. Radioactive particles spread over 7,000 square miles, falling on U.S. military personnel and the inhabitants of the Marshall Islands. National Archives photo no. 374-ANT-22-DPY-04-014.

Nuclear weapons cause devastating destruction and lasting toxicity–but the problem begins long before they explode. Building and testing of these weapons causes real harm to the health of living things and the environment, with women, children, and people of color bearing the brunt. Read on to understand the wide-reaching impacts of nuclear weapons.

Nuclear weapons are a humanitarian issue

Nuclear weapons are uniquely harmful to human health. In addition to the mass casualties caused directly by their explosions and the subsequent highly lethal fallout, nuclear weapons also release radioactive materials as they’re being built or tested. These unstable atoms can linger in the soil and atmosphere for centuries, and even millennia in some cases. No level of exposure is safe.

Nuclear weapons are made from uranium or plutonium, which is derived from uranium. Uranium miners and those living near mining sites suffer health impacts such as tuberculosis and lung cancer. In the United States, these people are primarily Native American.

A warning sign outside a uranium mine, photographed in 1972. National Archives photo no. 412-DA-1152.

Underground and above-ground testing of these weapons has created generations of “downwinders” — people who became ill from living downwind of testing sites. Workers in the U.S. nuclear weapons complex also suffer from exposure to radiation and harmful chemicals.

Although compensation programs for downwinders and nuclear workers exist, they are often limited and elusive; many who apply for these programs have had their claims denied.

One of these programs is the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which has provided more than $2.6 billion to people who have developed specified illnesses like cancer from nuclear weapons testing or production. When RECA was enacted in 1990, it notably did not cover downwinders in Utah, Idaho, Mohave County, Arizona, and New Mexico – including those affected by the Trinity Test. Activists worked for many years to fix these gaps and extended the program as it neared expiration in 2024. RECA lapsed for over a year before it was reinstated and expanded in 2025.

🔎 Additional resource

To learn more about the human impacts of nuclear weapons production and testing, read “Unknowing, Unwilling, and Uncompensated” by the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium.

Nuclear weapons are a racial justice issue

Locals in Bikini Atoll are forced to leave prior to nuclear tests. National Archives photo no. 374-ANT-CR-388-12.

The nuclear era has been inextricably tied to racism from day one. As nuclear weapons have been produced, tested, and used, communities of color have borne the brunt.

In 1945 the Trinity Test, the first ever detonation of a nuclear weapon, occurred in South Central New Mexico, an area populated with Indigenous and Latinx communities. Residents were neither informed nor protected from the effects of this explosion, and fought for nearly 80 years to receive compensation before finally becoming eligible for the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act in 2025.

While scientists involved in the Trinity Test took precautions against radiation exposure for their own staff, science historian Alex Wellerstein notes there was a lack of comparable concern for the Japanese civilians who would later be exposed. According to the book “African Americans Against the Bomb” by Vincent Intondi, African Americans were among the first to criticize Truman’s decision to drop the bomb. Some activists believe that racial bias played a role in the decision to bomb Japan, rather than Germany, and viewed nuclear weapons as a threat to freedom everywhere.

Throughout history, nuclear armed-nations like the U.S. continued to test nuclear weapons in areas inhabited by ethnic minorities. Over the course of nearly two decades, the U.S. conducted over 100 nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands and surrounding areas, known as the Pacific Proving Grounds. Inhabitants of these islands were forcibly removed from their homes, and experienced both acute radiation poisoning and long-term health consequences from this exposure.

All the while, the U.S. government was actively conducting biological and radiation exposure tests on Marshall Islanders. To this day, the U.S. government refuses to provide Medicaid to those affected.

The uranium used in U.S. nuclear weapons was mined both by forced labor in Belgian-occupied Congo, as well as by Navajo miners in the U.S, who were neither informed of nor protected from the health effects of working in radioactive mines. To this day, it is extremely difficult or impossible for these victims to get compensation.

Colonialist and hegemonic thinking continues to guide nuclear weapons policy today, with the United States and other nuclear armed nations holding the threat of nuclear violence over majority non-white countries, rather than through diplomacy, international cooperation and an understanding of global interdependence.

Working class communities of color would likely bear the brunt of a nuclear attack against the U.S., as weapons are more often designed to be used against urban areas, which contain higher proportions of communities of color. And even though a nuclear war would ultimately be a global catastrophe, western countries retain enormous sway over who has nuclear weapons and how many.

🔎 Additional resource

To learn more about nuclear weapons’ ties to racism, read “The Ultimate Coloniser: Challenging Racism and White Supremacy in Nuclear Weapons Policy Making,” from BASIC.

Nuclear weapons are an environmental issue

A concrete dome on Runit Island, known as the Runit Dome, stores dangerous waste from nuclear weapons tests. Photo by Underway In Ireland, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Since resource scarcity is the primary driver of political instability and conflict, climate change drastically increases the likelihood of a nuclear weapon being used. As regimes around the world attempt to grasp onto power in these unstable times, the temptation to develop nuclear weapons of their own in order to demonstrate their strength will only increase.

If even a small fraction of the world’s nuclear arsenals were to be used at the same time, the released soot and smoke would block sunlight from reaching the Earth’s surface for years, drastically reducing average global temperatures and leading to famine that would likely kill billions of people worldwide. A full scale nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia could put enough soot in the upper atmosphere to chill the ocean, alter sea currents, and cause an ice age lasting at least a decade, killing off most, if not all, of humanity.

Scientists have also found that even a single nuclear explosion could trigger ecological consequences that reach far beyond where the bomb went off. The radiation would spread through the air and water, affecting plants and animals by causing habitat loss, contaminating food resources, and disrupting reproduction. All of this could lead to species extinctions that disrupt the food chain and reverberate through the ecosystem.

Even if a nuclear war doesn’t happen, current methods for handling radioactive waste from testing and producing nuclear weapons are incompatible with the realities of climate change. The Runit Dome was constructed in the Marshall Islands to store 31 million cubic feet of nuclear waste collected from America’s Cold War-era nuclear weapons tests. That waste will remain hazardous for tens of thousands of years. Sea-level rise induced by climate change threatens the low-elevation islands, causing many to fear that the radioactive waste will begin leaking into the surrounding waters.

No one country can tackle either climate change or the threat of nuclear weapons alone. But both issues are existential threats to humanity, requiring us all to work together to mitigate the damage caused and prevent further harm.

🔎 Additional resource

To learn more, read “Potential Environmental Effects of Nuclear War” by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Nuclear weapons are a women’s rights issue

When nuclear weapons are used or tested, women and girls are disproportionately harmed. Research has shown that women exposed to radiation are more likely to experience cancer, heart disease, and stroke, compared to men. Studies on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki suggest women may be up to twice as likely to develop and die from solid cancer due to ionizing radiation exposure.

After various nuclear accidents where radioactive material was released into the environment, mental health problems were more prevalent in women, and especially mothers. These psychological impacts can exacerbate existing patterns of misogyny.

Despite all this, women are conspicuously under-represented when it comes to making decisions about nuclear weapons. While awareness of this disproportionate harm is growing, there is still a lot more to learn. Research on radiation exposure has historically been based on White men, excluding most people on Earth. Recent studies aiming to correct this oversight suggest that the greater percentage of reproductive tissue in the female body may contribute to the greater rate of radiation harm.

🔎 Additional resource

To learn more about how women are uniquely harmed by nuclear weapons, read “Gendered Impacts” by UNIDIR.

Nuclear weapons are a children’s safety issue

A boy from Kwajelein Atoll, part of the Marshall Islands, is examined. National Archives photo 374-ANT-22-C-260.

Nuclear weapons are designed to kill indiscriminately. This unfortunately means that, in a nuclear attack, innocent children will be among the many casualties.

Children are also more vulnerable to the impacts of a nuclear weapon for many reasons. Their bodies are smaller and frailer, making them more likely to die from the blast itself or to get trapped under collapsing rubble. Because children have thinner skin, they are also more susceptible to deadly burn injuries. In a growing body, cells are also growing and dividing more rapidly, increasing the odds of a child dying from radiation sickness or suffering from cancer and other diseases as a result of radiation exposure.

The children in Hiroshima and Nagasaki who survived the 1945 bombings often went on to lead difficult lives. They could be orphaned, carry psychological scars, and have a greater risk of developing cancer later in life.

In the Marshall Islands, where the United States tested powerful nuclear weapons during the cold war, local children and infants became sick from the ionizing radiation and nuclear ash that rained down across the Islands. The fallout resembled snow and children, unaware of the danger, played in it and developed acute radiation sickness.

🔎 Additional resource

To learn more about how nuclear weapons are uniquely harmful to children, read “The Impact of Nuclear Weapons on Children” by The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

The Know Nukes Quiz

Glossary

⬇️ Download this section (PDF)

This glossary defines key terms commonly used when talking about nuclear weapons, war, and diplomacy. Use it to help you navigate discussions about how nuclear weapons impact our world and what we can do about it.

Abolition

Abolition is the act of ending something. Nuclear abolition is the complete elimination of all existing nuclear weapons and the prohibition against developing or deploying nuclear weapons in the future.

Arsenal

An arsenal is the collection of weapons and military equipment that a group has. The term nuclear arsenal refers specifically to a nation’s collection of nuclear weapons.

Atom bomb

Atom bomb refers to nuclear weapons whose explosion is powered exclusively by the process of nuclear fission. The term is somewhat dated and also a misnomer, as the energy comes from the nucleus of the atom, so a more precise name is “nuclear fission weapon.” Atom bombs may also be known by the type of material used to trigger the fission reaction – for example, plutonium bombs use plutonium, while uranium bombs use uranium.

Ballistic missile

Ballistic missiles follow an arch-shaped trajectory to drop conventional or nuclear warheads on a target. They use rocket power in the first phase of their flight to achieve a high speed and altitude, and are carried by momentum to the peak of their arc and back down to the ground–all at very high speeds. Once the rocket-powered phase of a ballistic missile’s flight is over, its trajectory can no longer change.

The flight method and trajectory of ballistic missiles distinguish them from cruise missiles, which are powered by jet engines, similar to an airplane, and stay at lower altitudes. Cruise missiles have guided flight, but shorter ranges.

Although ballistic missiles can travel at hypersonic speeds, five times the speed of sound, they are not considered hypersonic missiles. Both are rocket-powered, but hypersonic missiles stay in the Earth’s atmosphere for most of their flight. After their initial launch, hypersonic missiles have a long-distance glide phase at low altitudes, where they can be slightly maneuvered and may get closer to their targets without being detected. Modern arsenals may also include hypersonic glide vehicles (HGVs), which are launched by ballistic missiles and then detach to glide.

Short-range ballistic missiles travel up to 1,000 kilometers, medium-range ballistic missiles travel up to 3,000 kilometers, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles can travel up to 5,500 kilometers. Intercontinental ballistic missiles, the largest and fastest kind, have a range greater than 5,500 kilometers.

Bilateral

Bilateral describes something involving two parties. In the world of international affairs, this typically refers to treaties or agreements made between two countries.

Bomber

Bombers are aircraft that drop bombs–conventional or nuclear–from the air onto a target. The United States maintains a fleet of 46 B-52 bombers and 20 B-2 nuclear bombers. As of 2025, the B-21 Raider is expected to enter deployment in the next few years.

Delivery system

Delivery systems, such as submarines, aircraft/bombers and missiles, are the mechanisms that carry or “deliver” a weapon to its intended target.

Deploy(ed)

Deployment is a military term signifying that a person, weapon or system is operational and ready for use. As of 2025, the United States has an arsenal of 1770 deployed nuclear weapons–1670 of which are strategic, and 100 of which are tactical.

Deterrence

Deterrence is the idea that the threat of violence and force can convince potential opponents not to engage in conflict–in other words, someone will not attack if the cost of doing so overshadows any possible gains. Nuclear deterrence is the theory that adversaries will not risk attacking a nation that may retaliate with nuclear weapons, nor risk attacking a nation being protected by a separate, nuclear-armed, nation. Critics argue that, over time, deterrence actually increases risk by normalizing the existence of nuclear weapons.

Disarmament

Disarmament is the act of either reducing or eliminating weapons. Nuclear disarmament refers to eliminating all nuclear weapons. Disarmament typically is an ongoing process guided by an agreement made between nations.

Entry into force

Entry into force is the point at which legal measures (like treaties, regulations, and legislation) gain legal force. Treaties, as an example, enter into force when they receive a minimum number of ratifications.

Fallout

Fallout refers to the harmful, and often deadly, radioactive material that is created and “falls out” of the sky after a nuclear weapon explodes. In the immediate aftermath of an explosion, fallout is mostly local and may descend as black rain. Because fallout can contain fine particles, it may also take months or years to settle, traveling anywhere in the world before it does so. People may get poisoned from contaminated crops and water supplies or may be directly exposed by inhaling, ingesting, or absorbing fallout through the skin. Fallout is produced whether a nuclear blast came from a weapon used in war, from a test explosion, or from an accidental explosion.

First strike

First strike refers to a calculated attack using one or more nuclear weapons that is not in response to another attack (i.e. it is preemptive). The strategic intent is often to disarm the opponent by significantly weakening or destroying their military power and hampering their ability to attack or retaliate.

First use

First use refers to the act of introducing nuclear weapons to a conflict. It could be in retaliation to an attack with a conventional weapon, and is likely a form of escalation.

Fission

Fission is a reaction that splits the nucleus of a heavy atom into two or more smaller nuclei. The process is usually triggered by bombarding the atom with neutrons, but fission can also be induced by protons, gamma rays, and other particles. The resulting reaction releases large amounts of kinetic energy, thermal energy, and radiation, and powers the explosion of nuclear weapons. Fission requires heavy, unstable nuclei, so uranium-235 and plutonium-239 are the most commonly used atoms. The newly split nuclei also releases neutrons, which may in turn split more nuclei, leading to a self-propogating nuclear chain reaction that rapidly releases massive amounts of energy.

Fusion

Fusion is a type of reaction that combines the nuclei of two light atoms into one slightly heavier nucleus. The process is induced by combining two hydrogen isotopes under sustained extremely high temperatures and pressure. When the nuclei fuse, they form one helium atom and a spare neutron. The process releases massive amounts of energy and is key to the explosion of a thermonuclear bomb, also known as a hydrogen bomb.

Golden Dome

The Golden Dome is a proposed missile-defense system introduced by President Donald Trump. It is intended to protect the United States by detecting and destroying threats like ballistic and cruise missiles.

Hair-trigger alert

Hair-trigger alert is a military policy that keeps nuclear weapons ready to launch within minutes of when an order is given. The U.S. keeps hundreds of missiles and submarine-based nuclear weapons on hair trigger alert staffed by around-the-clock crew.

This is also sometimes referred to as “launch on warning” or “launch under attack,” although some analysts consider them to be distinct: ”launch on warning” implies reacting to a weapon detected by radar, while “hair-trigger alert” refers to a general state of a high readiness.

Hydrogen bomb/Thermonuclear weapon

A hydrogen bomb, also known as an H-bomb or thermonuclear weapon, is powered by both nuclear fission and nuclear fusion and thus has an explosive force up to thousands of times more powerful than a nuclear weapon only powered by fission.

Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM)

Intercontinental ballistic missiles have larger range and speed than other types of ballistic missiles. ICBMs, which are designed specifically to carry nuclear weapons, can travel more than 5,500 kilometers and can reach most targets anywhere in the world in less than an hour. Modern missile designs can carry several warheads, which can be dropped on several targets. The United States maintains a fleet of 400 land-based Minuteman ICBMs.

Missile defense

Missile defense refers to a military system intended to shoot down missiles or drones. When the goal is to shoot down shorter range missiles, it is known as “theatre” or “battlefield missile defense.” If the system is intended to intercept and shoot down long-range missiles like cruise, ballistic, and hypersonic missiles, it is known as "strategic missile defense.” President Trump’s proposed “Golden Dome” would be categorized as a strategic missile defense system. Currently, there is no existing strategic missile defense system that can effectively stop or intercept a large-scale missile attack, especially since the attacker can deploy a number of tactics to confuse defenses.

Multilateral

Multilateral describes something involving three or more parties. In the world of international affairs, this typically refers to treaties or agreements made between three or more countries.

Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD)

Mutual Assured Destruction is the military principle that attacking a nuclear-armed nation with nuclear weapons will result in a nuclear war that destroys both sides. As an extension of the theory of deterrence, MAD assumes that the unacceptable risk will keep nations from using their nuclear weapons. The theory, which originated during the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, requires that neither side possesses a sufficient defense against nuclear weapons. While MAD is often presented as a stabilizing force, it has also been critiqued as destabilizing and strategically risky, especially when there are several nations involved.

New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START)

Signed in 2010, the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) is the only remaining treaty between the United States and Russia limiting the size of their nuclear arsenals and delivery systems. The treaty expires in February, 2026.

No-First-Use

No-First-Use is a commitment from a nuclear-armed nation to never use nuclear weapons first and only use them in response to a nuclear attack. China and India are the only two nuclear-armed nations that have adopted a no-first-use policy.

Non-proliferation

Non-proliferation generally refers to efforts to prevent the spread of all types of weapons. Nuclear non-proliferation specifically covers measures to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. This includes making sure those who already have nuclear weapons don’t develop more, as well as preventing nations from building, buying, or stealing nuclear weapons if they didn’t previously possess any.

Nuclear famine

Nuclear famine refers to the famine that would follow a round of nuclear attacks. The nuclear explosions would trigger firestorms, which would inject soot into the atmosphere and block a significant amount of sunlight for a prolonged period of time. This would drop global temperatures by several degrees and decimate global crop production, leading to mass starvation. Nuclear famine would likely result from even a relatively small number of nuclear weapons used anywhere in the world.

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)

The NPT is considered the cornerstone of nuclear arms control and efforts to prevent their spread of nuclear weapons and ultimately to eliminate them. All the world’s nations except Israel, Pakistan, India and North Korea are parties to the NPT – which commits non-nuclear weapons states not to develop nuclear weapons and the nuclear weapons states to pursue, in good faith, an agreement to eliminate their nuclear weapons.

Nuclear triad

Nuclear triad refers to the three types of nuclear weapon delivery systems that the United States deploys. It includes nuclear missiles based in land-based silos in several states in the Western United States, nuclear missiles deployed on submarines, and nuclear bombs deployed on long-range nuclear bombers.

Nuclear winter

Nuclear winter refers to the massive and sustained change in climate that would result from a large-scale nuclear war. Nuclear winter is usually used to describe the more severe and prolonged global cooling that would occur after a full scale nuclear war.

Retired nuclear weapon

A retired nuclear weapon is one that has been withdrawn from the nuclear stockpile. This does not necessarily indicate that the weapon has also been disassembled or destroyed. Key components, such as the deadly core, of a retired nuclear weapon may still be stored for future use.

Sole authority

Sole authority is the United States’ nuclear weapons policy which gives the U.S. president sole authority to order the launch of nuclear weapons. The president is not required to consult anybody, and nobody can legally challenge the decision.

Strategic nuclear weapons

Strategic nuclear weapons are large and designed to destroy targets anywhere in the world, often as part of an overall strategic plan to dominate an enemy nation. These powerful nuclear explosions can wipe out military bases, key infrastructure, entire cities, and many millions of people. Military strategy posits that these powerful weapons can “win” a war by swiftly decimating an opponent’s ability to wage war.

Submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM)

Submarine-launched ballistic missiles, as their names suggest, are ballistic missiles that are launched from submarines. Modern SLBMs are closely related to ICBMs and may also be intercontinental in range. The United States maintains a fleet of 14 Ohio-class nuclear submarines, each capable of carrying 20 Trident II D5 SLBMs. Each of these missiles can be loaded with multiple warheads.

Tactical nuclear weapon

Tactical nuclear weapons are designed for relatively short-range use–not across the world. They produce smaller explosions than strategic nuclear weapons do, but still have a tremendous amount of destructive power and generate a large amount of radiation. Some military tacticians posit that using a tactical nuclear weapon against military targets would not result in a nuclear response. Critics argue that by seeming more “usable,” tactical nuclear weapons provide a gateway to rapid nuclear escalation that could leave millions dead and injured.

Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)

Also known as the “nuclear ban treaty,” the TPNW is an historic international treaty, signed in 2017 at the United Nations, which “prohibits nations from developing, testing, producing, manufacturing, transferring, possessing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons, or allowing nuclear weapons to be stationed on their territory.” It is a legally binding treaty for those countries that have ratified it. It entered into force in January, 2021. As of June, 2025, 93 nations have signed the treaty and 74 have ratified it – representing a majority of the world’s population. Neither the United States nor any of the other 8 nuclear weapons states have signed or ratified the treaty.

Warhead

Warhead refers to the component of a weapon that explodes and causes destruction.